john.bernard.burke@gmail.com

ig johnburkeargh

Years ago, while viewing a photography exhibition at the Guggenheim, I came across the phrase “extrinsic meaning.” Essentially, it refers to any meaning derived from information outside the artwork itself—titles, statements, wall text, and other contextual details.

The images leaned heavily on abstraction, while the remaining works used tight crops, collage, and overlays to block out and reduce additional visual context. I found the phrase helpful, but it also suggested something uneasy to me. How much meaning should one gather outside a work of art to determine its significance? And how much of this extrinsic information may be a method of dictating meaning or even a sales pitch framed through academic rhetoric?

Furthermore, when language rather than image usurps meaning and authority in the visual arts—lessening the audience’s participation—how successful has the artwork truly been? Or are these various texts and statements works of art in their own right, deserving to be judged by an entirely different set of criteria?

All artists, in one form or another, perform a game of hide and seek with the viewer. We reveal fragments of ourselves, leaving the rest for the viewer to complete on their own terms and, subsequently, take part in the play of creation. Tension exists here, a kind of division of labor between artist and audience. When it works, there’s a moment of meeting between the artist and the viewer, a recognition beyond words but one that demands strong participation.

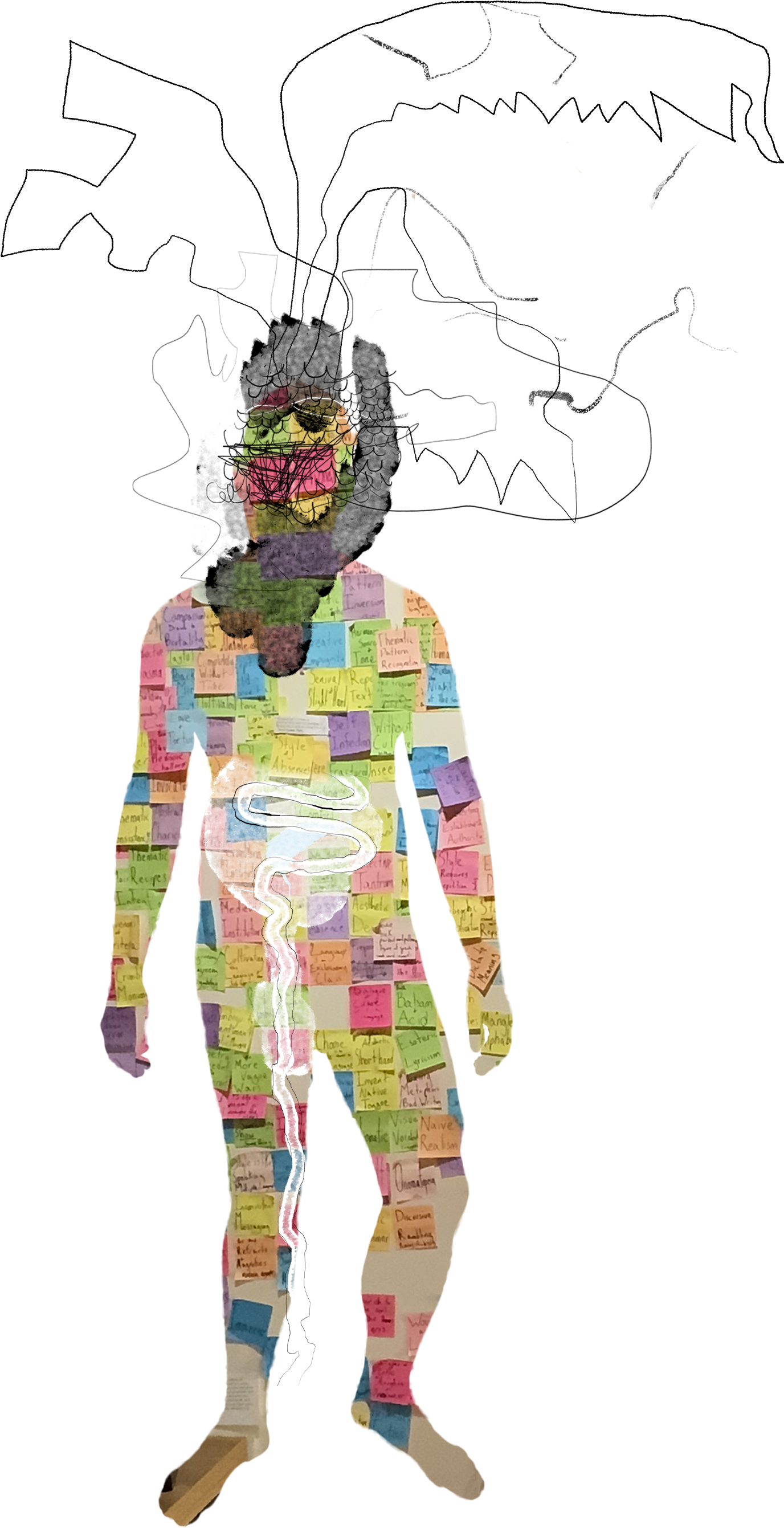

Christopher Bollas spoke of the ‘unthought known,’ describing the way pre-verbal experiences become internalized. He thought of these traces as ‘strange cargo,’ elements from our past that we carry within the self.

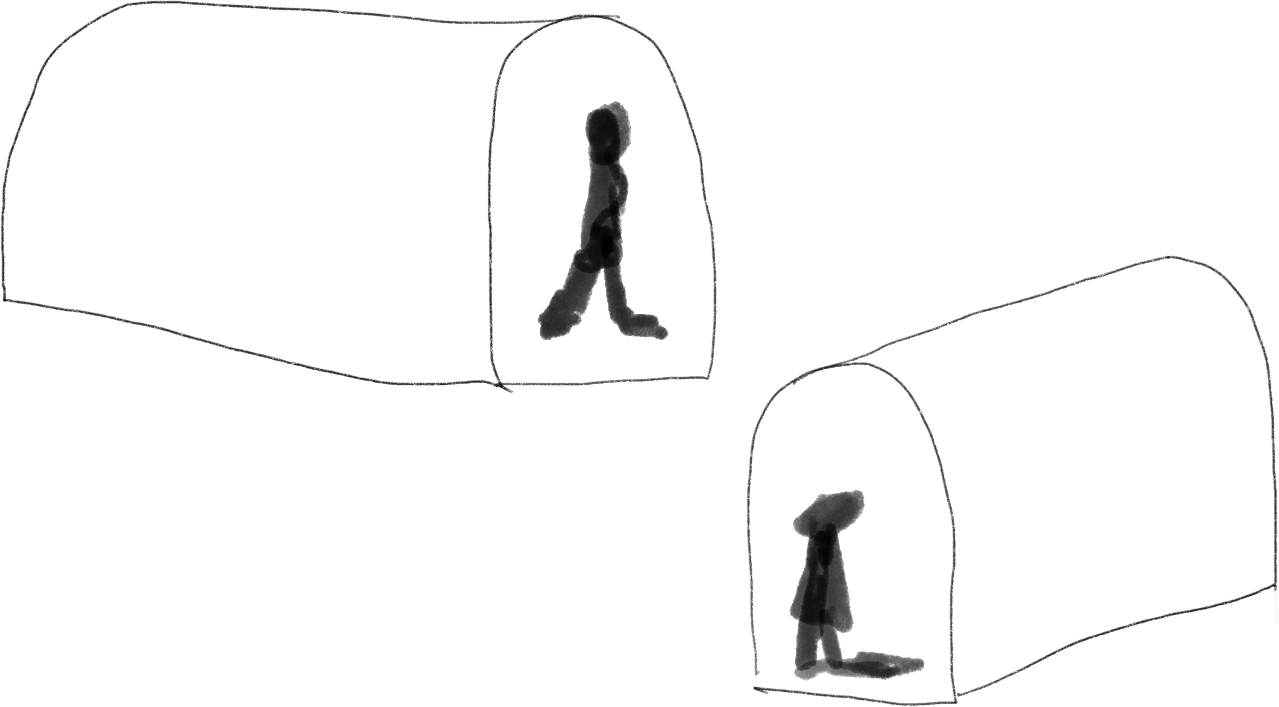

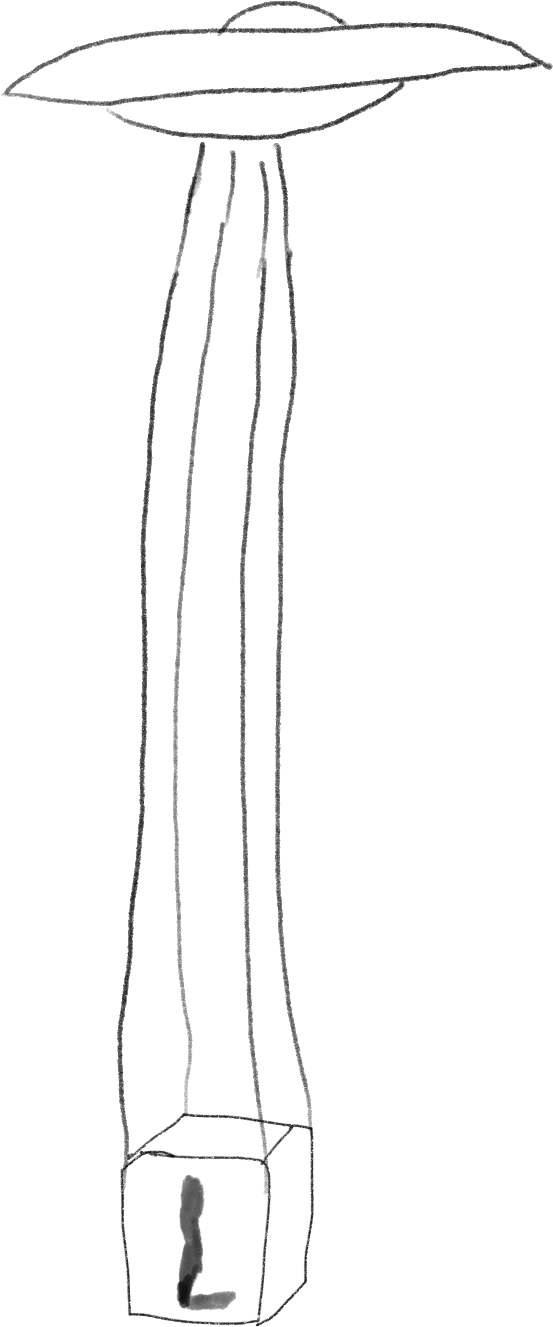

I see my own work as grappling with these accumulated fragments. Themes of excess and absence, mourning and mania pervade many of the images. In making these, I recognize a cast of characters: excessive, ghoulish, cartoonish, and tragic.

Character, as a container for these qualities and moods, proves easier to depict than absence. Absence can only exist through removal, a mute non-presence that carries the tension of a vacuum. The challenge is determining how to shape what embodies so little. Really, two options remain: to leave the void bare and exposed or summon something to fill what has vanished.

I have plenty of theories about my work. But as I’ve tried to elucidate, there’s a tipping point from which language begins destroying what it claims to reveal. In Winnicott’s words, “It is a joy to be hidden, and a disaster not to be found.” Those drawn to visual art aren’t looking to be found through language. Language has never been the homeland. Much like hide and seek, the ideal viewer becomes a silent co-conspirator with the artist, both playing while searching in semi-darkness.

John Burke